9 experts reflect on the US reaching 200,000 Covid-19 deaths

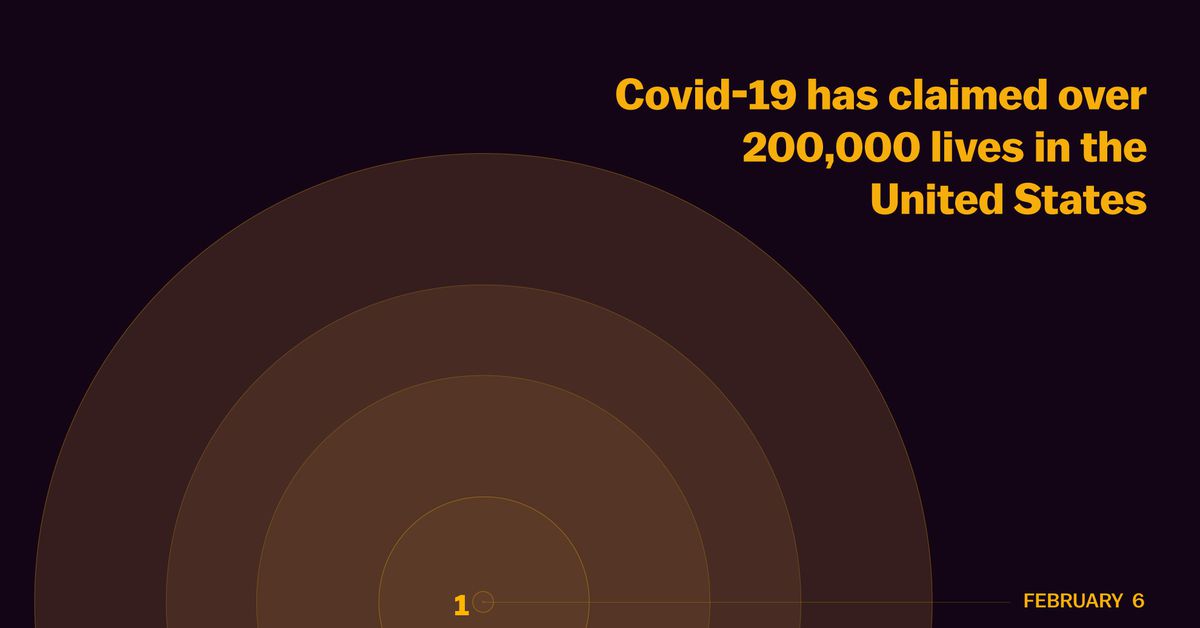

This week, the number of Americans confirmed to have died from Covid-19 crossed 200,000. It is a staggering loss of life, and this unfortunate milestone warrants some reflection.

In that spirit, I asked a question of several of the public health experts whose knowledge I have relied upon over the last six months: If you had been told back in February (when the first Covid-19 death in the US was recorded) that before the end of September 200,000 more people would be dead, what would your reaction have been?

“I thought we would be much more resilient in our public health, our policymaking, and trust in public health leaders,” Albert Ko, a Yale School of Public Health professor, told me. “I would have thought we would have done a better job protecting our nursing homes.”

I thought I would share the responses in full, with some light editing for clarity.

Jennifer Kates, director of global health and HIV policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation:

My February self was indeed worried. Things were escalating fast and I increasingly believed, from reviewing the emerging data, that the U.S. was barreling toward treacherous territory. However, I in no way envisioned we would get to 200,000 deaths. In part because that was not (yet) the scale being discussed but also because this was not inevitable. Many of these deaths could have been prevented, if the response had been different.

Josh Michaud, associate director for global health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation:

It was really hard in February to imagine there would be 200,000 dead in the US in a matter of months. After all, the first state emergency declaration in the US didn’t come until the end of February (in Washington), and we didn’t know the extent of the disease in Italy, Iran, and other places. It wasn’t until March that the Imperial College model was released (projecting the potential for a million deaths or more in the US), the NBA shut down, Tom Hanks was infected, etc. We didn’t know about the US testing debacle yet. Stay-at-home orders were not yet being talked about. So back in February I don’t think it had dawned on most just how bad things could get.

Even so, looking back it’s clear that many US deaths could have been prevented with a different national course of action and it’s not like 200,000 deaths was a foregone conclusion at all.

David Rehkopf, a social epidemiologist at Stanford University:

There are a lot of proximal reasons here specific to how we didn’t react, how people didn’t take it seriously, the lack of universal health care, the distrust of government right now, lack of a clear message that really matter.

But I’d like to point out that the US is currently 46th in the world in terms of life expectancy. So why would COVID-19 deaths be any different? All of these same factors that impact our COVID prevalence and COVID deaths also are in many ways similar to what leads to our higher overall deaths as well.

But what is important to realize is that is wasn’t always this way in the US. From 1975-1980, we were 17th in the world in life expectancy. But there has been a slow (and recently not so slow) decline since the early 1980s.

David Celentano, chair of Johns Hopkins University’s epidemiology department:

Shocked – that would be the word that I would say captures my response to our current death numbers from the vantage point of February. By mid-March we were locked down. The doubling time of numbers of infections has truly shown we are not serious in regard to a national approach to COVID-19. This represents the failure of the national leadership, the failings of the executive branch, the emasculation and politicization of the CDC and FDA, and the skepticism of science by large segments of the public, egged on by the president. My guess is that we will be at 400,000 by the close of the year; I certainly hope not.

Kumi Smith, an epidemiology professor at the University of Minnesota:

The things that have surprised me most in hindsight:

- That it took so long for the US CDC to develop and distribute a test. Precious time was lost as they tried to recover from the first failed test; this set us on a whole different epidemic trajectory.

- That the White House would ever try to assume the role of public health messenger to the public. And that the CDC has taken as much of a back seat as it has. There’s a protocol for issuing out consistent and up-to-date public health messaging to the public but you wouldn’t know it from how things have gone.

- That mask wearing would become so politicized (though someone did recently share with me a story about anti-maskers during the 1918 pandemic so maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised).

If you take into account all of these things, the death toll is sadly not all that surprising.

Eleanor Murray, a Boston University epidemiologist:

In February, I was definitely watching COVID carefully, but I also felt confident that the administration would activate a coordinated epidemic response and that such a response would control the spread of the virus relatively quickly and successfully. Clearly I was very wrong about that. Not only was there no clear coordinated response, many of the pandemic preparations that had been made over the previous two decades had been scrapped, canceled, or left to lapse/ expire, making it difficult for other levels of government to step in to the leadership void.

I made a tweet sometime in February in response to someone asking for a prediction of what COVID would look like that said something like: right now our best guess for what will happen is to look at historical examples of similar outbreaks – those are SARS & MERS and both were pretty much contained by one year out; not at all like the 1918 flu.

I still think that at the time that was a reasonable prediction, given what we knew, but it’s clear that the pandemic has not played out like SARS or MERS. Some of that has to do with features of the virus – the presence of pre-symptomatic spread makes control much harder for SARS-CoV-2 than for SARS. But a lot of it has to do with failures in response.

Tara Smith, an epidemiologist at Kent State University:

In February, I knew 200,000 deaths were theoretically possible, but I honestly didn’t believe we’d get to that point. Surely we’d get it under control well before that level of mortality, right? I hadn’t anticipated not only the lack of federal response, but the active undermining of our federal scientific leadership within the CDC, FDA, and NIH. I had expected a potentially bumpy road, and resistance from anti-science folk (though I anticipated that being directed toward the vaccine; I hadn’t considered mask mandates in February), but not this level of dysfunction that we’ve seen only amplify since early in the epidemic.

Caitlin Rivers, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security:

I think we started off on the wrong foot with our struggles to scale diagnostic testing and identify cases. By the time community transmission was first recognized, I think we already had substantial outbreaks underway. We fell behind and have struggled to catch up ever since, though for more reasons than just diagnostic testing shortages. There have been gaps in the federal response, notably a lack of clear overall strategy. Although state and local leaders have done the best they can, I think a lack of a national approach has held us back.

Natalie Dean, a biostatistician at the University of Florida:

In the spring, I participated in a series of expert surveys facilitated by Nick Reich and colleagues at UMass. I was able to look back and see what I had put for predictions. My May predictions for the year-end totals are below. So by December, we will likely exceed my 90th percentile prediction.

It is sad. I expected that this would be challenging, but I didn’t expect how desensitized we as a country would become to over 1,000 Americans dying a day. The goalposts keep moving, and what once seemed unimaginable is now a daily reality. Sometimes I think it is worth reminding people that we have various models to forecast cumulative deaths, but infectious diseases are not the weather. What ultimately will happen depends upon our actions, and so much more death does not need to be foretold. What more can we be doing to keep people safe? Be it testing, tracing, ventilation, mask-wearing, finding safer alternatives to activities. And demanding greater action from our politicians to make this possible.

This story appears in VoxCare, a newsletter from Vox on the latest twists and turns in America’s health care debate. Sign up to get VoxCare in your inbox along with more health care stats and news.

Help keep Vox free for all

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world: Contribute today from as little as $3.

tinyurlis.gdclck.ruulvis.netshrtco.de